Sermon on Good Friday 2020

The Revd Canon Chris Newlands, Vicar of Lancaster

HOLY WEEK 2020 ADDRESS 5. GOOD FRIDAY – THE CRUCIFIXION

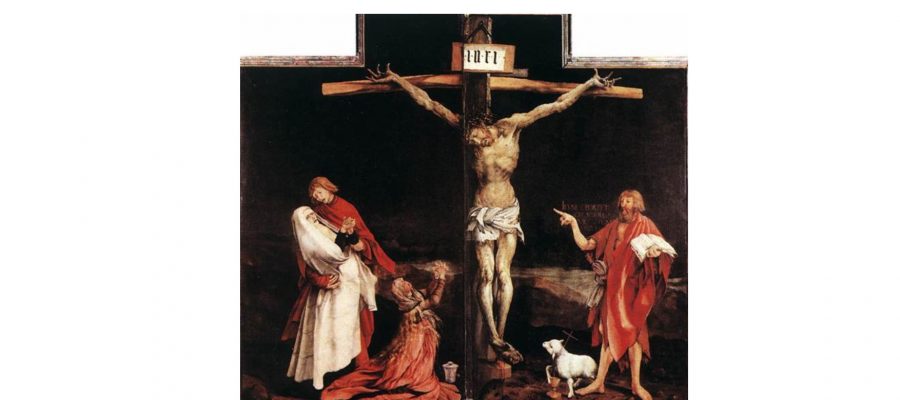

The crucifixion scene on the closed centre panel of the altarpiece is one of the most moving depictions of the crucifixion in Western art. It is not rendered “polite” or innocuous, because the crucifixion itself was neither polite nor sanitised. It was a brutal execution, and although it is shocking to our eyes, so used to Victorian or portrayals of the scene that are designed not to cause offence, it seeks to depict the pain and suffering inflicted on Christ in the manner of his death.

As it was created for victims of St Anthony’s Fire – that cruel disease which caused people long and painful suffering, simply because they had unknowingly eaten bread which was prepared using a rye which had been attacked by a parasitic fungus known as ergot – it is a brutally honest depiction of a dead body, alike so many other dead bodies which would have been sadly commonplace in the Isenheim Hospital. The discolouration of the body of Jesus resembled the discolouration of their own bodies when they succumbed to the worst ravages of the disease, and gangrene set in to their legs and arms.

The altarpiece is not quite symmetrical – the cross is offset slightly, because the two panels open outwards from the centre, and it would have been unthinkable for that to have been through the body of Jesus. But what has happened is surely no coincidence, for when the panels are opened, it separates the right arm of Jesus from his body – in the same way people who suffered gangrene often had their limbs amputated. Incidentally, this was one of the first recorded example of amputations taking place in western medicine. Amputating a limb, although without doubt a life-changing event, could ultimately save the life of the person. It has even been suggested that removing Jesus’ arm by opening the crucifixion panel opens up a more glorious Resurrection for people – as the painting behind this is the Resurrection panel which we will be looking at on Easter Day.

Christ dominates the scene, with only the four witnesses present: the Mother of Jesus held up by St John the Beloved Disciple, Mary Magdalene, and John the Baptist and the Lamb. There is no sign of the others we knew were also present – no Romans, no mocking Pharisees, no curious bystanders, and of course, no other victims on crosses – the two thieves we know were crucified alongside him. The focus is entirely on Jesus in this moment of his saving death. That is emphasised by the change in scale, the body of Jesus is considerably larger than any of the others; Mary Magdalene, on her knees below the cross is much smaller than everyone else.

The sky is black, and there are no weeping angels present as there are in many other depictions of the crucifixion. The focus of our attention is of course, the body of Christ on the cross.

We see there the cross itself almost struggling to bear the weight of the world’s Redeemer, as the crossbeam, where we plainly see the mark of the tools revealing the flat surface of the beam, which seems to bend downward because of the weight it bears.

The body of Jesus has been savagely beaten, not just using whips, but also with thorns as the cuts of the thorns reveal – in many places the thorns remain embedded in his body, in his arms, his torso, even his feet. Even his loincloth is in tatters, torn by the blows of the whips and thorns. (Remember how that was prefigured by the swaddling clothes that were work by the infant Jesus in the portrait of the Virgin and Child in the second image of the series).

The eyes are drawn, to the hands of Jesus – where the palms are pierced by the nails, as are his feet. Those hands speak of the extreme and unbearable pain he suffered as the nails were hammered through onto the rough-hewn wood of the cross beam. The fingers are tensed in a paroxysm of pain. These hands that were present in the moments of creation with the Father, and “flung stars into space” have been surrendered to these cruel nails.

The painting marks the final moment of the crucifixion scene. Jesus is dead, and his lifeless body is like any other lifeless body – lacking the colours of life, and displaying the colours of decay – his lips have turned blue and his head has fallen onto his ribcage.

It is finished.

Unapologetic in its depiction of a brutal death, this portrait stays with us – until we are presented with a better image of Jesus in his new and risen life. This is what we wait for, this is what we are anticipating in these days of waiting, hoping, and praying.

The words he had told his disciples foretelling that he would rise on the third day seemed to be little comfort – especially to those who had seen him die. And there was no doubt at all that he had really died!

Through Lent, and especially through this season of Passiontide and the Holy Week of Our Lord’s Passion, we have followed Jesus preparing himself, preparing his disciples, preparing us for this moment. Do we believe he will rise again? We have confidence that his Resurrection will come on Easter Day – but that was by no means a certainty in the minds of those first disciples and witnesses.

The readings we have read as part of our preparations have been challenging, as they deal with the difficult issues of life and death – a very present reality for us all now, as fear grips the nation in the light of this pandemic.

But as we heard these words from the Bible readings, the psalms, and the Gospels, although this is a very new and destabilising experience for all of us – in the history of the Priory this is nothing new, and in God’s Providence we know that we will come through this period, terrible though it may be – and after the darkness and sorrow of suffering and death, comes a joyful celebration of life – richer and more abundant than it ever was.

In anticipation of this we look forward even more fervently than ever before to the joyous celebration of our Lord’s Resurrection and the eternal life he offers to all who believe.

Amen.

Latest News

ANNOUNCEMENT: SUFFRAGAN BISHOP OF DONCASTER

Announcement It has been announced by 10 Downing Street this morning...

Read More...EPIC CYCLING PILGRIMAGE: JONATHAN MAYES, CEO OF CATHEDRALS TRUST, VISITS LANCASTER PRIORY

On Monday 19th May, the Cathedrals Trust CEO visited Lancaster...

Read More...The Lord's Prayer Tour with the Archbishop of York: Sunday 8th June at 4.30pm

As part of The Lord’s Prayer Tour across the...

Read More...