Sermon on Holy Monday 2020

The Revd Canon Chris Newlands, Vicar of Lancaster

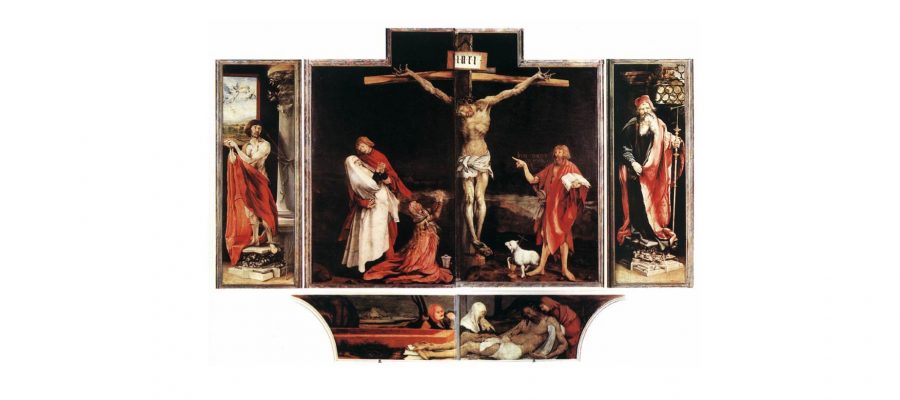

HOLY WEEK ADDRESS 2020 – THE ISENHEIM ALTARPIECE

- INTRODUCTION

Last year we holidayed with family in Alsace, in Eastern France. We spent a day in Colmar, a beautiful ancient city with beautiful churches, buildings and lots to see.

But when we arrived in the main square, the first thing that caught my eye was a sign to the Musée Unterlinden, which houses the extraordinary work of art, the Isenheim Altarpiece.

My first glimpse of a detail of this enormous work of art was way back in my student days, when I bought a recording of the St Matthew Passion: the LP had the central panel of the crucifixion as its front cover, and the dramatic impact of that depiction of the crucifixion seemed to be a perfect match for the drama of the music of Bach, which is, for many, a timeless and perfect setting of the Passion narrative. However Bach’s music was written over two hundred years after the Isenheim altarpiece was painted. I decided way back then that I wanted to do a series of Holy Week addresses based on scenes from this astonishing work of art.

Little did I know then, that Holy Week 2020 would be such an unusual keeping of this most Holy period in the church year. But neither did I know how unusually appropriate this work of art would be to our present circumstances.

To explain that, I need to let you know a little about how it came to be created.

Isenheim (now known as Issenheim) is a village in Alsace which is at the moment a part of France, but has in the past been a part of Germany or the Holy Roman Empire before that. It is just a small village, but in the early 16th Century it was home to a hospital run by the Anthonite order, which was a very significant place. This hospital was under the patronage of St Anthony, and it was a very wealthy institution, as it was on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela, or Rome.

There was one unique element of the hospital in Isenheim: it received patients who suffered from a disease known as “St Anthony’s fire.” This was a terrible disease, also known as ergotism, which was characterized by an intense burning sensation in the limbs. The most extreme manifestation was gangrene in the arms and legs, with discolouration and very painful symptoms. The cause of this was not discovered for several centuries, so people kept arriving to be treated in the Isenheim Hospital. It was eventually discovered to have been caused by eating bread which was made by flour which had been contaminated by the parasitic ergot fungus.

In order to receive treatment, the sick had to renounce all their possessions, and swear abstinence, and loyalty to the community at the hospital. They would receive a habit to wear, and a wine-based drink “le saint vinage” (holy wine) made of wine – into which the relics of St Anthony had been dipped, and then mixed with medicinal herbs, speedwell, poppy, gentian, vervain, nettles – some of which had anaesthetic or healing properties. They were also given bread and meat.

These treatments, of balms, and drink had some anti-inflammatory properties, but often limbs were amputated in the hope of stopping the spread of the disease. For many people, septicaemia set in and was often the cause of death. The last cases in France were recorded as recently as the 1950s.

What has this got to do with the altarpiece?

The victims of St Anthony’s fire did suffer terribly from their afflictions, and many died. However, according to the prevailing theology of the time, they were shown the image of Jesus dying on the cross in agony, and told that their suffering is as nothing in comparison with Christ suffering for them. Indeed, as the creator of the altarpiece would have been in residence in the Hospital in Isenheim as he painted it, he would also have witnessed at first hand the sufferings of the patients with St Anthony’s fire and their treatment; he would have seen the effects of gangrene on their bodies – and the image of Jesus he painted bears some of the marks of that terrible disease.

As the patients would have attended mass daily from the altar with this impressive painting behind it, and the image of the dead Christ being laid in the tomb, this would have reminded them of their own mortality, and their kinship with Jesus, whose sufferings were like theirs.

They would also pray to St Anthony, who is depicted in the panel to the right, who, it was believed, could heal them from the sickness which bore his name. On the other side is St Sebastian, who was the saint to whom people prayed to be delivered from plague.

Let me say a little about the artist who created this – he was for many years known as Matthias Grünewald, also known as Mathis Gothart Nithart. He has become somewhat a legendary figure in art. There is even a Symphony which Hindemith wrote with the name “Mathis der Maler” – it takes an image from the altarpiece as the inspiration for each of the three movements.

The altarpiece was created in around four years, beginning in 1512, and it was completed in 1516 just one year before Martin Luther’s launching of the Reformation with the 95 theses attacking the corruption of the Roman Catholic Church. So it was the very last flowering of religious art in the High German Gothic style before the Reformation, and has even been called “Germany’s Sistine Chapel”. Miraculously, it survived the iconoclasts of the Reformation and even the French Revolution, only some elements were lost and presumably destroyed. It originally had a “crown” a great gothic flowering of carved pillars – not dissimilar from the Priory’s own choirstalls, in fact, though it was gilded to look like pure gold. When it was intact with its crown, the whole altarpiece would have stood 10 metres high. If you can remember the Moon in Lancaster Priory – that was 7 metres in diameter. So if you can imagine the whole work being half as big again as the Moon installation, and you will have an idea of just how imposing this would have been in its original state! Unfortunately, the “crown” was left behind in Isenheim when the painted panels were moved to safety in Colmar at the time of the French Revolution, and subsequently destroyed.

Grunewald did the paintings – and they are truly miraculous in concept and execution. But he did not build the construction which displays it. This was another highly skilled craftsman by the name of Nikolaus Hagenuer, whose engineering skills produced a frame with panels which open and close on themselves to reveal a multiplicity of images. The image of the crucifixion opens up from the centre, the two large wings opening outwards to reveal a very different image which we will look at tomorrow, based on the Virgin Mary. Then that image also opens up from the centre, to reveal a gorgeous gilded set of statues which lie behind the other images, of St Anthony surrounded by saints, while the outer panels show scenes from the life of St Anthony, the patron of the hospital, above the altar itself – the depiction of the burial of Jesus can be removed to show instead carvings of Christ with the twelve disciples.

The addresses from now to Easter Day will be based on different scenes, or details of this altarpiece, most of them based on the altarpiece in the “closed” position, as you can see in today’s image on the website. They tell the story from the Archangel Gabriel’s visit to the Blessed Virgin Mary through the Passion of Christ, to his glorious Resurrection, and I hope that reflecting on these powerful images will help us to accompany Christ as he flows the Way that leads to the Cross, and opens for us the gateway to salvation.

Amen.

Latest News

ANNOUNCEMENT: SUFFRAGAN BISHOP OF DONCASTER

Announcement It has been announced by 10 Downing Street this morning...

Read More...EPIC CYCLING PILGRIMAGE: JONATHAN MAYES, CEO OF CATHEDRALS TRUST, VISITS LANCASTER PRIORY

On Monday 19th May, the Cathedrals Trust CEO visited Lancaster...

Read More...The Lord's Prayer Tour with the Archbishop of York: Sunday 8th June at 4.30pm

As part of The Lord’s Prayer Tour across the...

Read More...